EP2: Networking in Linux - Routing Deep Dive

When we talk about routing, we often picture routers, firewalls, and network appliances moving traffic across large networks. But Linux itself is a router. Every Linux system makes routing decisions, even if it only has a single network interface.

Every time an application sends a packet, the Linux kernel decides where that packet should go. Sometimes the traffic stays local. Sometimes it leaves through a specific interface. In other cases, it must be forwarded to another network entirely. All of those decisions are made using the same routing logic, regardless of whether the system is acting as a simple workstation or as a multi-homed router.

This article looks at routing from the perspective of a single Linux host. We focus on how the kernel determines reachability and selects paths for outgoing traffic, working step by step through routes, scopes, routing tables, policy-based routing, and routing marks.

Rather than jumping straight into commands, the emphasis is on how routing decisions are made inside the kernel and how those decisions affect where packets actually go. Understanding this flow makes it easier to reason about routing behaviour, especially once systems become multi-homed or start handling traffic for other networks.

Routing vs Forwarding

Routing and forwarding are closely related, but they are not the same thing.

Routing is the decision-making process. It is about determining the best path a packet should take based on the information available to the kernel.

Forwarding is the action. It is the act of moving a packet from one network interface to another, or delivering it locally when the destination belongs to the system itself.

By default, Linux does not forward packets between interfaces. This is intentional. A server should not accidentally behave like a router. When packet forwarding is enabled, Linux becomes capable of moving traffic between networks, but it still relies on routing information to decide how that traffic should flow.

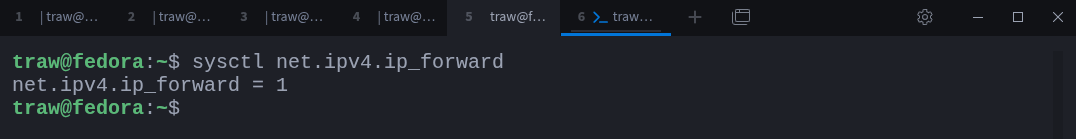

To check whether IPv4 packet forwarding is enabled, you can use:

$ sysctl net.ipv4.ip_forwardIf the output is 0, packet forwarding is disabled. If the output is 1, packet forwarding is enabled.

To enable packet forwarding temporarily, you can write directly to the kernel parameter:

$ echo 1 > /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forwardOr use sysctl:

$ sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1Both methods take effect immediately, but the change does not persist across reboots.

To make packet forwarding permanent, add the following line to a drop-in file under /etc/sysctl.d/. You can choose any filename, but it is common to prefix it with a number, for example 99-ip-forward.conf:

net.ipv4.ip_forward = 1Then apply the configuration:

$ sudo sysctl -pOnce a packet arrives on an interface, the kernel must answer a simple question:

Is this packet meant for me, or should it be sent somewhere else?

Routing determines the answer. Forwarding is what happens next.

IP Destination Classes

From the kernel’s point of view, every destination IP falls into one of three categories. This classification happens early and shapes every routing decision that follows.

Local destinations are IP addresses assigned to the system itself. This includes interface addresses and the loopback range.

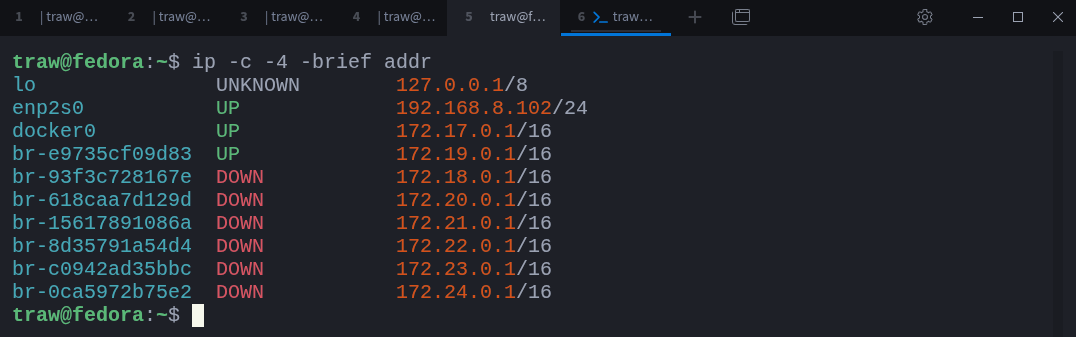

You can see local destinations by inspecting interface addresses:

$ ip -c -4 -brief addrEach address shown here represents traffic that terminates on the local machine. The loopback interface deserves special attention: the entire 127.0.0.0/8 range points back to the system itself and is commonly used for local testing and inter-process communication.

If you are coming from Cisco or Juniper, these are typically referred to as local routes, and they usually appear as /32 host routes in routing tables.

Connected networks are networks that are directly reachable through a local interface. If an interface is configured with an address in a given subnet, Linux knows that any IP within that subnet can be reached without a router.

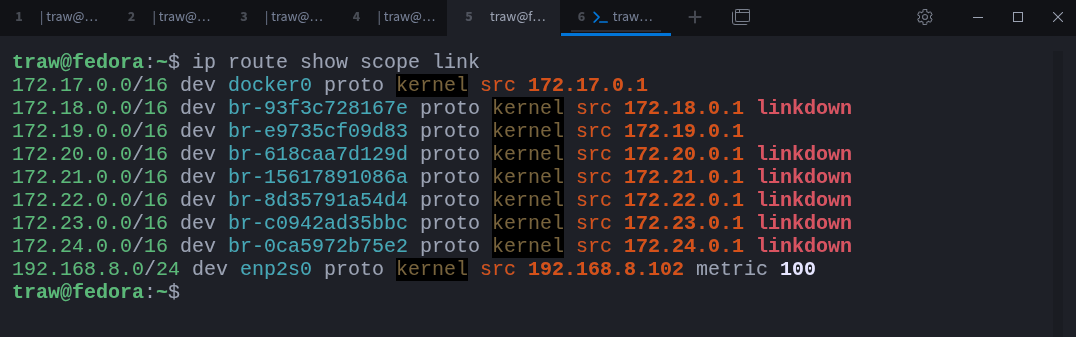

You can view connected networks with:

$ ip route show scope linkThese routes tell the kernel which networks are reachable directly and through which interface. Traffic destined for any of these networks is sent straight out of the corresponding interface, without involving a gateway.

For example, traffic to 192.168.8.1 is sent directly out of enp2s0.

If you come from Cisco or Juniper environments, these are known as connected routes. Notice the use of scope link here; we will revisit scopes in more detail shortly.

Remote networks include everything else. If a destination is neither local nor directly connected, Linux must send the packet to a router that is directly reachable.

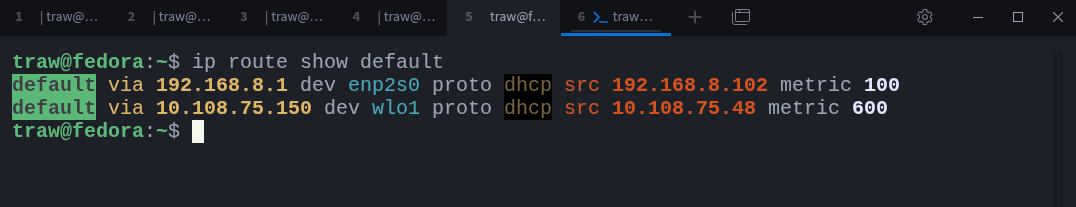

These routers are typically represented by default routes:

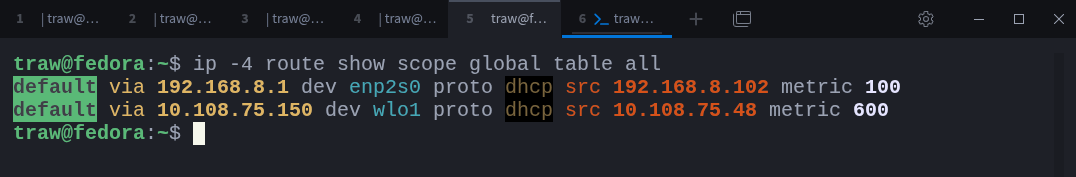

$ ip route show defaultIn this case, the system has two default routes, one per interface. Linux will not use both arbitrarily. Instead, it compares their metrics and selects the preferred path. We will look at route selection and metrics in detail later.

This classification is fundamental. Before the kernel evaluates metrics or chooses a gateway, it first determines whether a destination is local, connected, or remote.

Sysxplore is an indie, reader-supported publication.

I break down complex technical concepts in a straightforward way, making them easy to grasp. A lot of research goes into every piece to ensure the information you read is as accurate and practical as possible.

To support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber and join the growing community of tech professionals.

What are Routes

A route is simply an instruction that tells the kernel how to reach a destination.

At a minimum, a route answers three questions:

Which destination does this apply to?

Where should the packet go next?

Which interface should be used?

In Linux, a route is made up of a few core components:

Destination

This can be a single IP address (a host route), a subnet (a network route), or a catch-all default route (

0.0.0.0/0).Next hop

This is the IP address of the next router the packet should be sent to. If the destination is directly connected, no next hop is required.

Interface

This is the local network interface the packet will exit from.

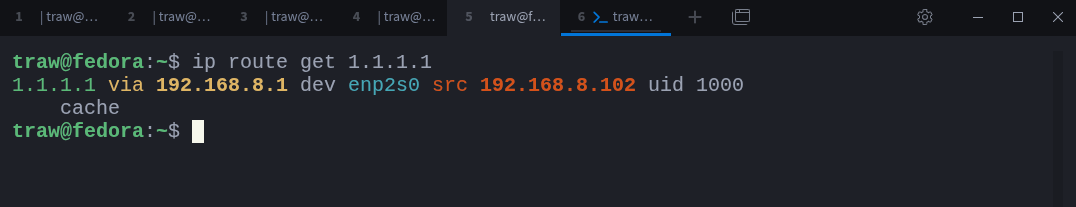

You can see how the kernel interprets a route decision using ip route get. For example:

$ ip route get 1.1.1.1This output shows the full routing decision for that destination:

1.1.1.1is the destination address.192.168.8.1is the next hop (gateway).enp2s0is the interface used to send the packet.192.168.8.102is the source address chosen for the packet.uid 1000indicates which user initiated the traffic.

There are additional routing attributes, such as metrics and routing tables, weight, which we will look at later. For now, the important point is that this is the final decision the kernel has made for that packet.

If the destination belongs to a directly connected network, there is no next hop. The packet is sent straight out of the appropriate interface.

If the destination is remote, the route must specify a gateway. That gateway itself must be reachable through a directly connected network. Linux will never forward traffic to a next hop it cannot already reach.

Routes are not guesses or suggestions. They are explicit rules the kernel follows when deciding where packets should go.

Route Scopes

Route scopes describe how far a route can “see”. They define the visibility of a route and place boundaries on where it can be used. These scopes map directly to the destination classes we discussed earlier.

Linux primarily uses three scopes: host, link, and global.

Host scope routes apply only to addresses on the local machine. These include interface IP addresses and the loopback range. Traffic matching a host-scope route never leaves the system and never involves packet forwarding.

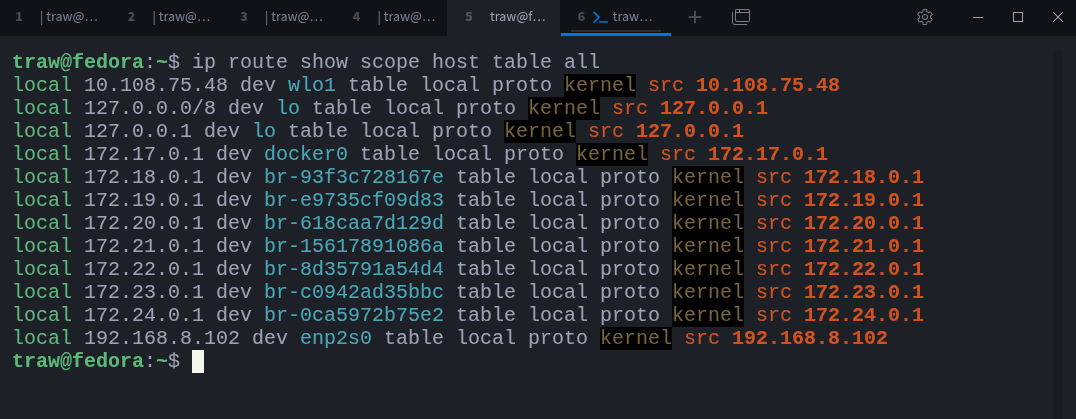

You can inspect host-scope routes across all routing tables with:

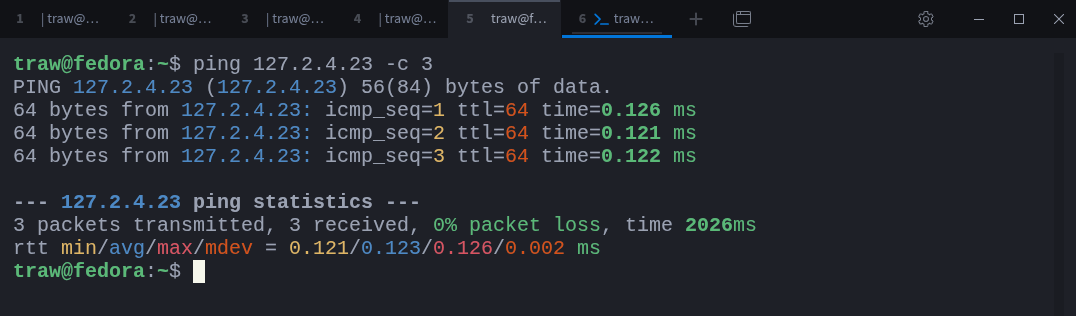

$ ip route show scope host table allThe loopback range appears as 127.0.0.0/8 because it is treated as a special local network. Any address within that range will always resolve back to the local system:

$ ping 127.2.4.23 -c 3Even though the address looks arbitrary, the traffic never leaves the host.

Link scope routes apply to directly connected networks. These routes are used for destinations that can be reached without passing through a router. Traffic matching a link-scope route is sent directly out of the associated interface.

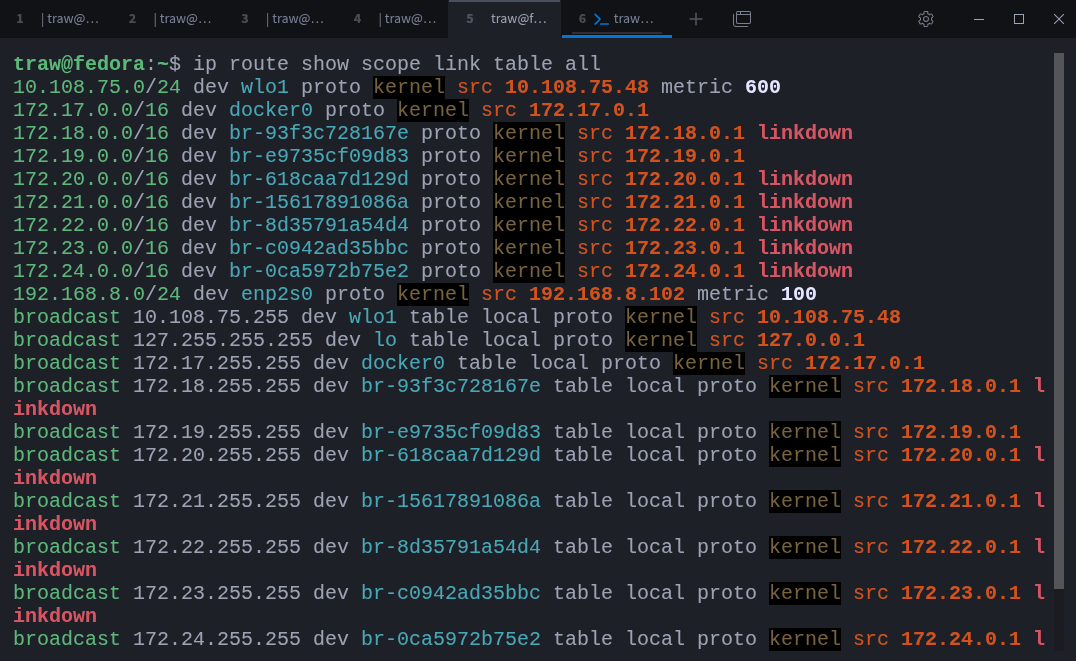

You can view link-scope routes with:

$ ip route show scope link table allAlongside unicast routes, you’ll also see broadcast routes. Broadcast addresses target all hosts on a local network segment and are automatically created by the kernel for each connected network.

Global scope routes apply to destinations beyond the local system and its directly connected networks. These routes require one or more routers to reach the final destination. The default route is the most common example.

You can identify global-scope routes with:

$ ip -4 route show scope global table allThese routes act as catch-all paths for traffic that does not match any more specific destination.

Route scopes are not cosmetic labels. They allow the kernel to quickly eliminate routes that cannot possibly apply to a given destination, making route selection faster and more predictable.

Routing Tables

Linux does not store all routes in a single flat list. Instead, routes are grouped into routing tables. Each table represents a separate set of routing decisions that the kernel can consult when processing a packet.

You may have already noticed this in earlier commands, where we used table all to display routes from every table at once. By default, however, most commands operate on a single table unless told otherwise.