What are Subshells in Linux

In Linux, every time you open a terminal, you start a shell, usually Bash or Zsh. But what happens when you run a command inside parentheses, like this?

$ (pwd; ls)You’ve just created a subshell, a new child shell that runs your commands in isolation from the parent. Subshells are one of those shell concepts that quietly do a lot behind the scenes in Bash. They make it possible to run commands in separate environments, capture output safely, and even perform parallel processing , all without interfering with the main shell session.

While subshells exist in most Unix-like shells, this guide focuses on how they work in Bash, how they behave, how to create them, and how to make use them in your everyday command-line work.

What Exactly Is a Subshell?

A subshell, sometimes called a child shell, is simply a new instance of the shell that runs inside your current one. It inherits the environment and variables from the parent shell but runs as a separate process.

Think of it like opening a smaller sandbox inside your main shell, whatever you do inside stays there. Any variable changes, new functions, or settings you define in a subshell disappear once it exits. The parent shell remains untouched.

When a subshell is created, it runs independently, which means you can safely experiment or run commands without worrying about altering the main shell’s state.

Creating a Subshell

There are several ways to create a subshell in Bash, each useful in different situations.

Using Parentheses

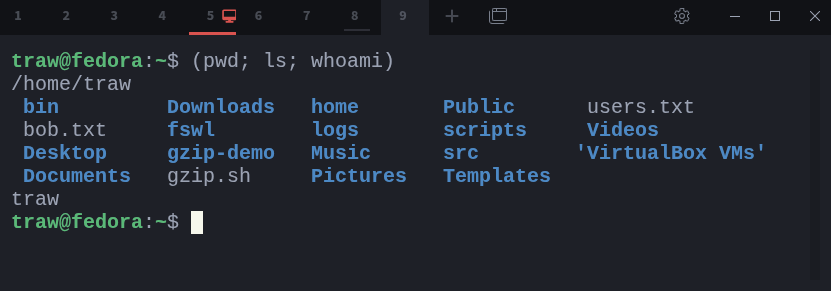

The simplest way is to wrap a group of commands in parentheses (). Bash will run everything inside them in a separate subshell.

$ (pwd; ls; whoami)Each command runs in an isolated environment, and once the subshell exits, you’re back in the parent shell.

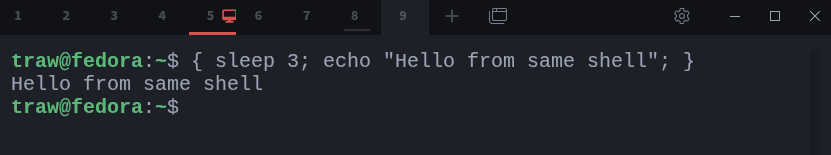

It’s important to note that curly braces {} might look similar, but they behave differently, they don’t create a subshell. Commands inside braces run in the current shell.

$ { sleep 3; echo "Hello from same shell"; }To make this clear, think of parentheses as “run this somewhere else” and braces as “run this right here.” Many new Bash users mix these two up, so it’s worth remembering:

()creates a subshell;{}doesn’t.

We’ll look at how to confirm when a subshell has been spawned in a later section.

Command Substitution

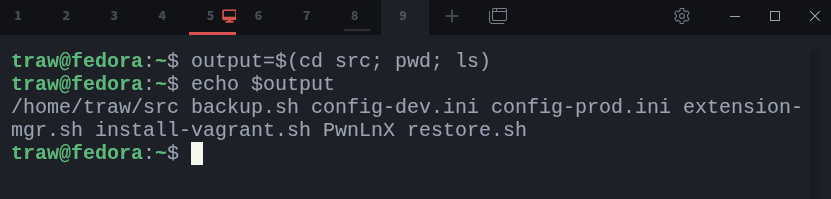

Another common way to create a subshell is through command substitution, where the output of a command is captured and stored in a variable.

$ output=$(cd src; pwd; ls)

$ echo $outputEverything inside $() runs in a subshell. The result is then returned to the parent shell as plain text. This is why variable assignments or environment changes inside $() don’t persist afterward.

Explicit Subshell Invocation

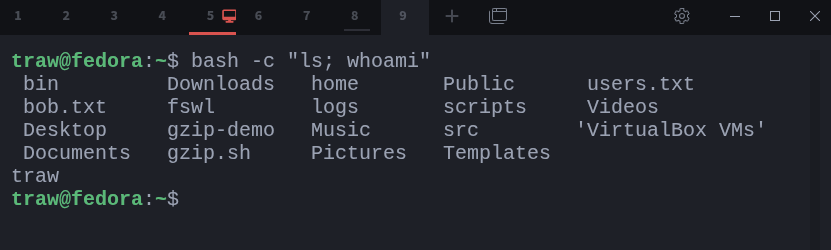

You can also explicitly launch a new Bash process and tell it what to run using the bash -c command.

$ bash -c "ls; whoami"This approach is less common in everyday scripting but useful when you need fine control over how commands are executed, especially in automation scripts or debugging scenarios.

Relationship Between Parent Shell and Subshell

A subshell is always spawned by a parent shell, and the two share a parent–child relationship. The subshell inherits all environment variables, functions, and settings from its parent, but any changes made inside it stay local. Once the subshell ends, those changes disappear , the parent shell continues as if nothing happened.

Here’s a quick demonstration:

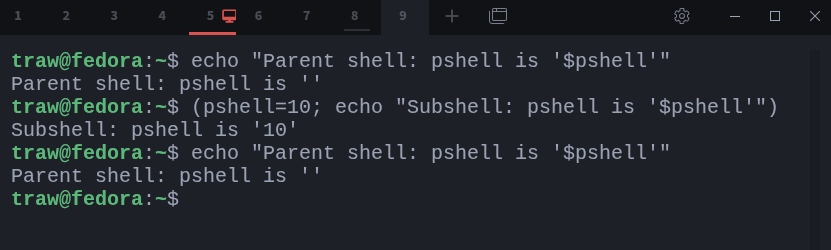

$ echo "Parent shell: pshell is '$pshell'"

$ (pshell=10; echo "Subshell: pshell is '$pshell'")

$ echo "Parent shell: pshell is '$pshell'"In this example, the variable pshell is first unset in the parent shell, meaning it has no value. Within the subshell created by the parentheses(), we assigned the value 10 to the variable pshell , and print its value. However, after the subshell terminates, the parent shell’s value ofpshell remains unset, demonstrating the isolation of the subshell’s environment.

It’s important to note that subshells isolate the environment and affect the scope of variables and functions defined within them. Variables and functions defined in a subshell are not accessible outside of that subshell, even if the subshell is part of a larger script or function.

Sysxplore is an indie, reader-supported publication.

I break down complex technical concepts in a straightforward way, making them easy to grasp. A lot of research goes into every piece to ensure the information you read is as accurate and practical as possible.

To support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber and join the growing community of tech professionals.

How to Check if a Subshell Has Been Spawned

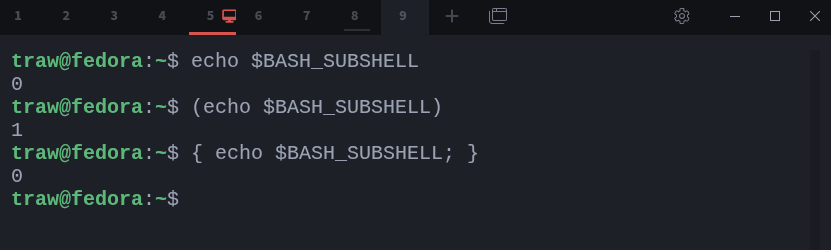

You can tell whether you’re in a subshell by checking the value of the special variable $BASH_SUBSHELL. In the main shell, this variable is set to 0. Each time a new subshell is created, the value increases by one.

$ echo $BASH_SUBSHELL

0 # parent shell

$ (echo $BASH_SUBSHELL)

1 # first subshell

$ { echo $BASH_SUBSHELL; }

0 # parent subshellThis is a simple and reliable way to confirm that a command or script is running in a separate shell instance.

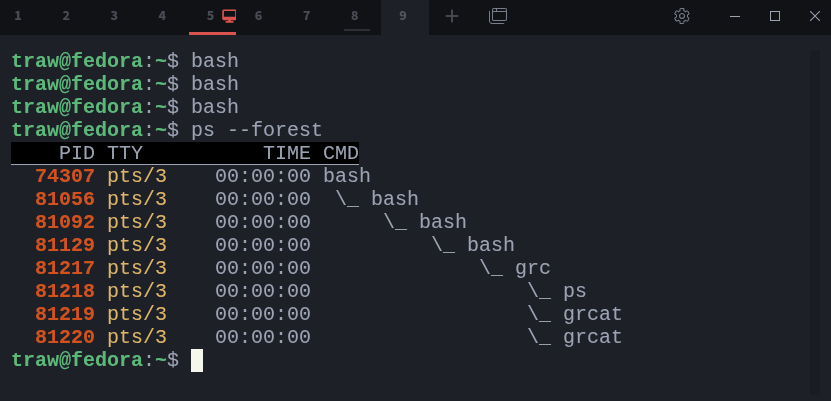

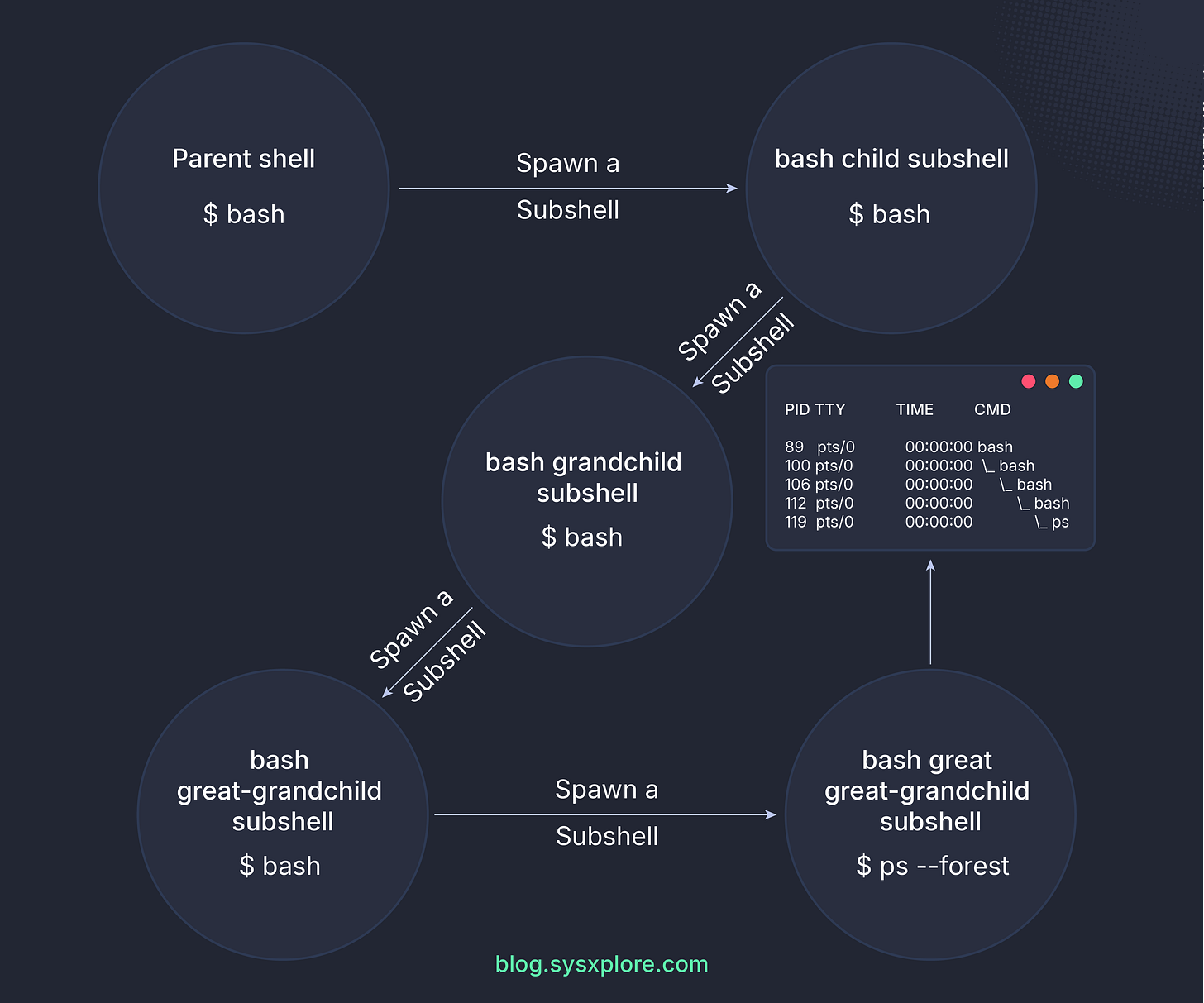

Another handy method is to visualize shell hierarchy using the ps --forest command:

$ bash

$ bash

$ bash

$ ps --forestThis command displays a tree view of all processes, showing how each subshell branches out from its parent. You’ll see nested bash processes, each representing a different subshell level.

Each time you type bash, you create a new shell running inside the previous one. The ps --forest command displays a clear tree of these nested sessions.

To exit back up the chain, simply type exit or press Ctrl+D until you return to your original shell prompt.

Nested Subshells

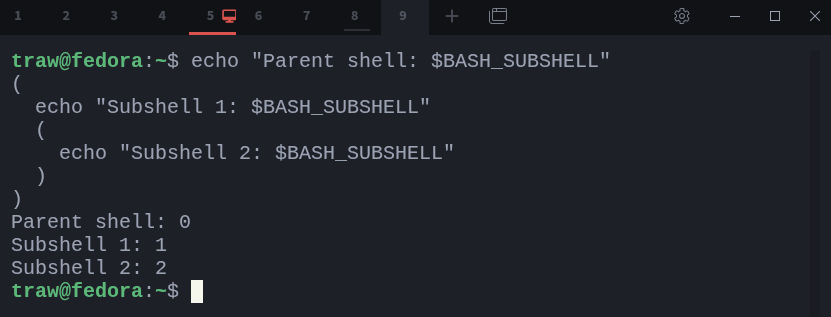

Subshells can also create other subshells, forming a nested hierarchy. Each new subshell inherits its environment from the one above it, and the $BASH_SUBSHELL variable increases by one with every new layer.

$ echo "Parent shell: $BASH_SUBSHELL"

(

echo "Subshell 1: $BASH_SUBSHELL"

(

echo "Subshell 2: $BASH_SUBSHELL"

)

)When you run this, you’ll see that each level reports a higher value for $BASH_SUBSHELL, showing how deep you are in the nesting.

Do Shell Scripts Run in Subshells?

Yes, they do — by default, every shell script runs in its own subshell. When you execute a script, Bash spawns a new shell process to run it. This means any variable changes or environment modifications inside the script don’t affect your current shell session once the script finishes.

For example:

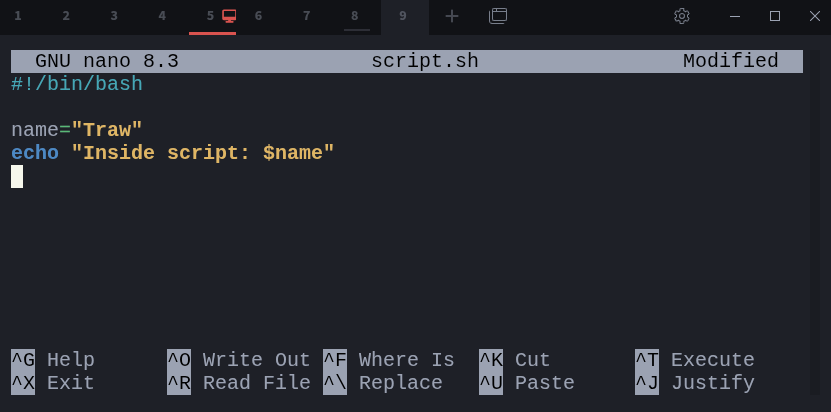

$ nano script.sh

#!/bin/bash

name="Traw"

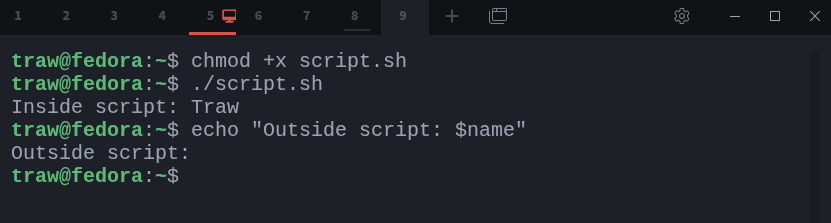

echo "Inside script: $name"$ chmod +x script.sh

$ ./script.sh

Inside script: Traw

$ echo "Outside script: $name"The variable name exists only inside the script’s subshell. Once the script exits, the parent shell has no knowledge of it.

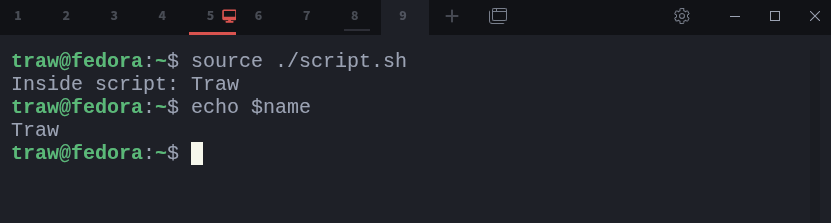

If you want a script to run in the current shell instead of a subshell, use the source command or the dot (.) builtin. These execute the script in the same shell process, so any changes made inside persist afterward.

$ source ./script.sh

$ echo $nameAlternatively, you can use the exec command to replace the current shell process entirely with another command or script. Unlike running a script normally, exec doesn’t spawn a subshell — it takes over the current shell. Once the command finishes, there’s no returning to the previous shell because it no longer exists.

$ exec ./script.shIn this example, the current shell is replaced by the script process. When the script ends, the shell session terminates because it has been replaced completely.

Making Use of Subshells

Subshells aren’t just an abstract concept, they’re incredibly practical once you understand where to use them. You can take advantage of their isolation to run commands independently, manage background jobs, or perform tasks in parallel.

Running Commands in the Background

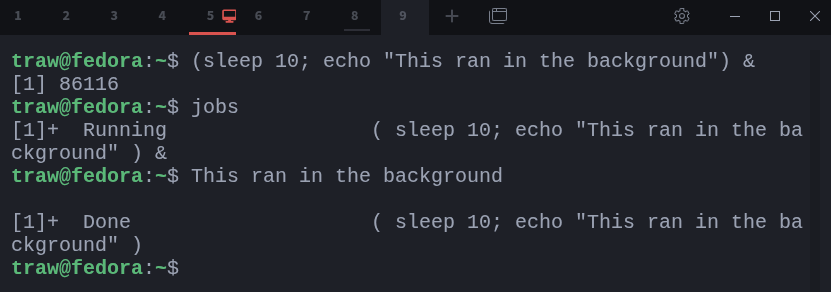

When you enclose commands in parentheses and append an ampersand (&), the subshell runs in the background while you continue working in the parent shell.

$ (sleep 10; echo "This ran in the background") &Here, the commands inside the parentheses execute in a separate subshell, leaving your main prompt free for other work. When the subshell finishes, it prints the message to your terminal.

Co-processing

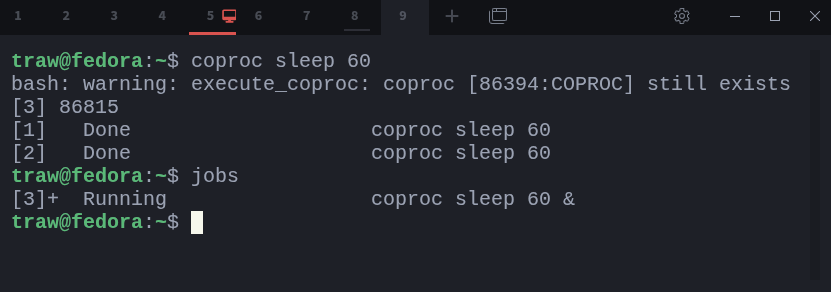

A co-process is another case where Bash automatically creates a subshell. It runs a command asynchronously and gives you a two-way communication channel with it, handy for scripts that need parallel execution or interaction between processes.

$ coproc sleep 60This starts sleep 60 in the background as a co-process. You can then interact with it using special file descriptors (${COPROC[0]} and ${COPROC[1]}) if needed.

Parallel Processing with Subshells

You can also use subshells to run multiple tasks simultaneously. By combining parentheses with the & operator, each task runs independently, allowing Bash to execute them in parallel.

$ (task1.sh) & (task2.sh) & (task3.sh) &

$ waitEach script runs in its own subshell, freeing the parent shell to continue once all tasks are done. The wait command ensures that the parent shell pauses until every background process has completed.

This technique is especially useful for automation scripts where you need to process multiple files, network requests, or computations at once.

Why You Should Sometimes Avoid Using Subshells in Bash

While subshells are powerful and versatile, they aren’t always the right tool for the job. Every time you create one, Bash spawns a new process, and that comes with a bit of overhead. In scripts that use subshells excessively, this can add up and slightly slow things down.

Another common pitfall is losing changes made inside the subshell. Since a subshell runs in isolation, any variable assignments, directory changes, or environment modifications made there disappear as soon as it exits. This can lead to confusing behavior if you expect those changes to persist in the parent shell.

Excessive use of subshells can also make scripts harder to follow. When each block of code runs in its own isolated environment, debugging or understanding the script’s state becomes more complicated. And in resource-limited systems, spawning many subshells at once can consume unnecessary memory and file descriptors.

In short, use subshells deliberately. They’re great when you need isolation or parallelism, but if your goal is to modify the current environment or maintain state between commands, stay in the parent shell instead.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this content, don’t forget to leave a comment, like ❤️ and subscribe to get more posts like this every week.

Okay, I am going to need someone to explain this to me..... like I am a child 🥹