Part 1: SSH Tunnels Deep Dive - Local Port Forwarding

Most people only use SSH for logging into a remote machine, and they never look beyond that. But SSH can do far more than provide a secure shell. One of its most powerful but overlooked features is tunneling, the ability to move traffic through an encrypted channel and reach services you normally can’t access.

This becomes incredibly useful once you start dealing with servers behind firewalls, private subnets, or NAT boundaries. A service might be running somewhere in the network, but you have no direct way of reaching it. With SSH tunneling, you don’t need to expose ports publicly or ask for firewall changes, you simply reuse the SSH connection you already have.

Think of an SSH session as a secure pipe. Normally, you use it to send commands. But that same pipe can carry anything: database requests, web traffic, API calls, as long as it’s TCP. SSH gives you the flexibility to redirect that traffic in different directions depending on what you need to reach.

At first, SSH tunnels feel confusing. That’s normal. Many admins and developers struggle with them until they see them demonstrated in real scenarios and work through them hands-on. That’s the goal of this series: to break down SSH tunneling into clear, practical parts, each one supported by labs you can run on your own machine. All the lab files are available in the GitHub repository.

This series will cover the four major types of SSH tunnels:

Local Port Forwarding

Remote Port Forwarding

Proxy Tunneling through a Bastion Host

Dynamic Port Forwarding (SOCKS5)

Each part focuses on one pattern, explains when it’s useful, and walks you through a complete lab environment that demonstrates the behaviour step by step.

In this first part, we’ll start with the most familiar one, Local Port Forwarding, and see how a simple SSH connection can give you access to services that would normally be unreachable.

Local Port Forwarding

Local port forwarding is usually the first tunneling feature people encounter because it feels intuitive: you open a port on your own machine, and any traffic you send to that port gets delivered to a service running somewhere else. Nothing about the service changes. It still listens on its normal port, on its own network, but your laptop gains a private, encrypted shortcut straight to it.

A useful way to think about local forwarding is to imagine you’re standing outside a building. You can’t walk in, but you can open a small window on your side and slide data through it. SSH takes whatever goes into that window and carries it to the room you specify inside the building. From your local machine’s point of view, the service looks like it’s running right on your laptop, even if it’s actually behind several layers of restrictions.

One common situation where a local tunnel becomes invaluable is when you’re on a network where a server allows SSH access but blocks everything else, no HTTP, no HTTPS, nothing. Maybe the service you need is a website running on port 80 or 8080, but the firewall won’t let you reach it directly. Instead of requesting firewall changes or exposing the service publicly, you simply open an SSH local tunnel. Your HTTP traffic then rides inside the encrypted SSH connection and reaches the webserver without being blocked.

Let’s jump into the lab and see this in action.

Lab Setup

I have two machines set up:

Client – 192.168.60.10 (this is where I’ll run my SSH command)

Webserver – 192.168.60.11 (this machine is running a simple website and allows SSH access)

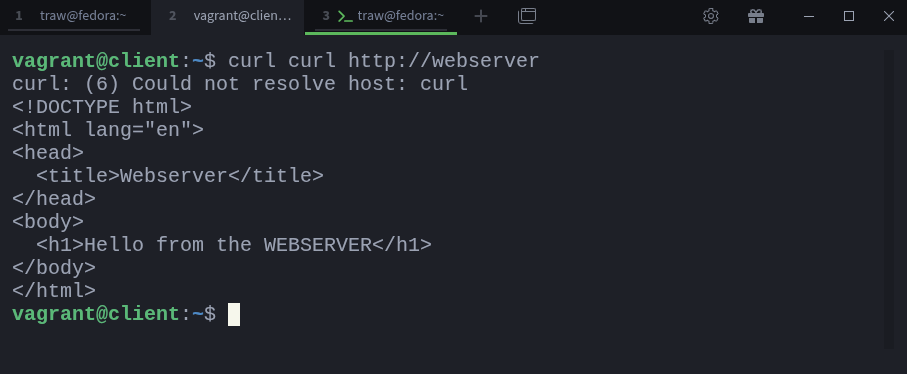

For now, the client can still access the webserver directly over HTTP. We’ll simulate a firewall blocking this access shortly. But first, let’s confirm the webserver is actually reachable, from the client run:

$ vagrant ssh client

$ curl http://webserverAs you can see, the webserver responds normally.

Simulating a Firewall Block

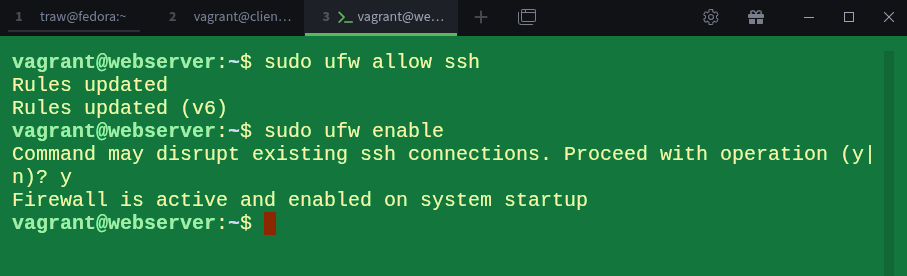

Now, let’s block all incoming traffic on the webserver except SSH. We’ll do this by setting a simple firewall rule on the webserver:

$ vagrant ssh webserver

$ sudo ufw allow ssh

$ sudo ufw enableI allowed SSH before enabling the firewall. The reason is simple: when UFW is enabled, any traffic that doesn’t match an allow rule is blocked by an implicit deny at the bottom of the rule list. If we enabled the firewall first without allowing SSH, we would lock ourselves out. By allowing SSH beforehand, we make sure we can still access the machine.

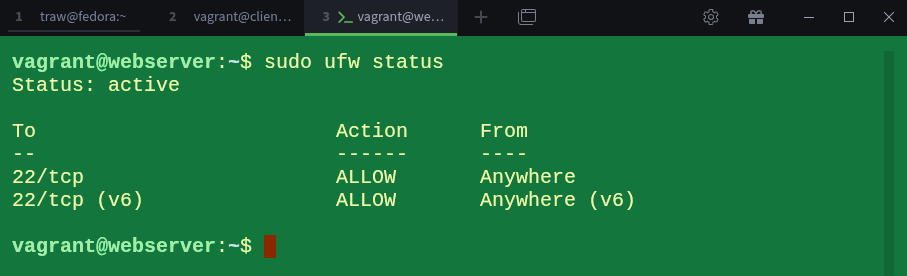

Let’s confirm that the firewall is active:

$ sudo ufw statusOur firewall is now running. If we try accessing the webserver over HTTP again from the client, it should fail:

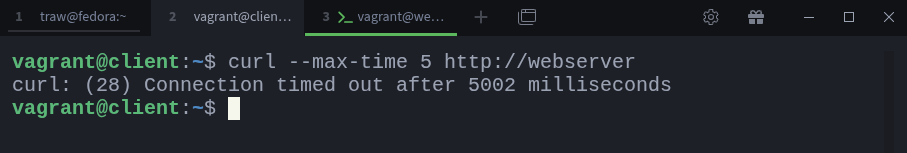

$ curl --max-time 5 http://webserverAs expected, the connection times out because the firewall is blocking HTTP traffic.

NOTE:

I added the

--max-time 5option to the curl command to prevent it from hanging indefinitely while waiting for a response. This is useful here because we know the connection will fail due to the firewall rule.

Creating the Local SSH Tunnel

Since we still need to reach the webserver, let’s set up a local SSH tunnel. This will forward a local port on the client machine directly to the webserver’s HTTP port through the existing SSH connection.

Now let’s set up the client, but before we run the command, here’s the syntax for local port forwarding:

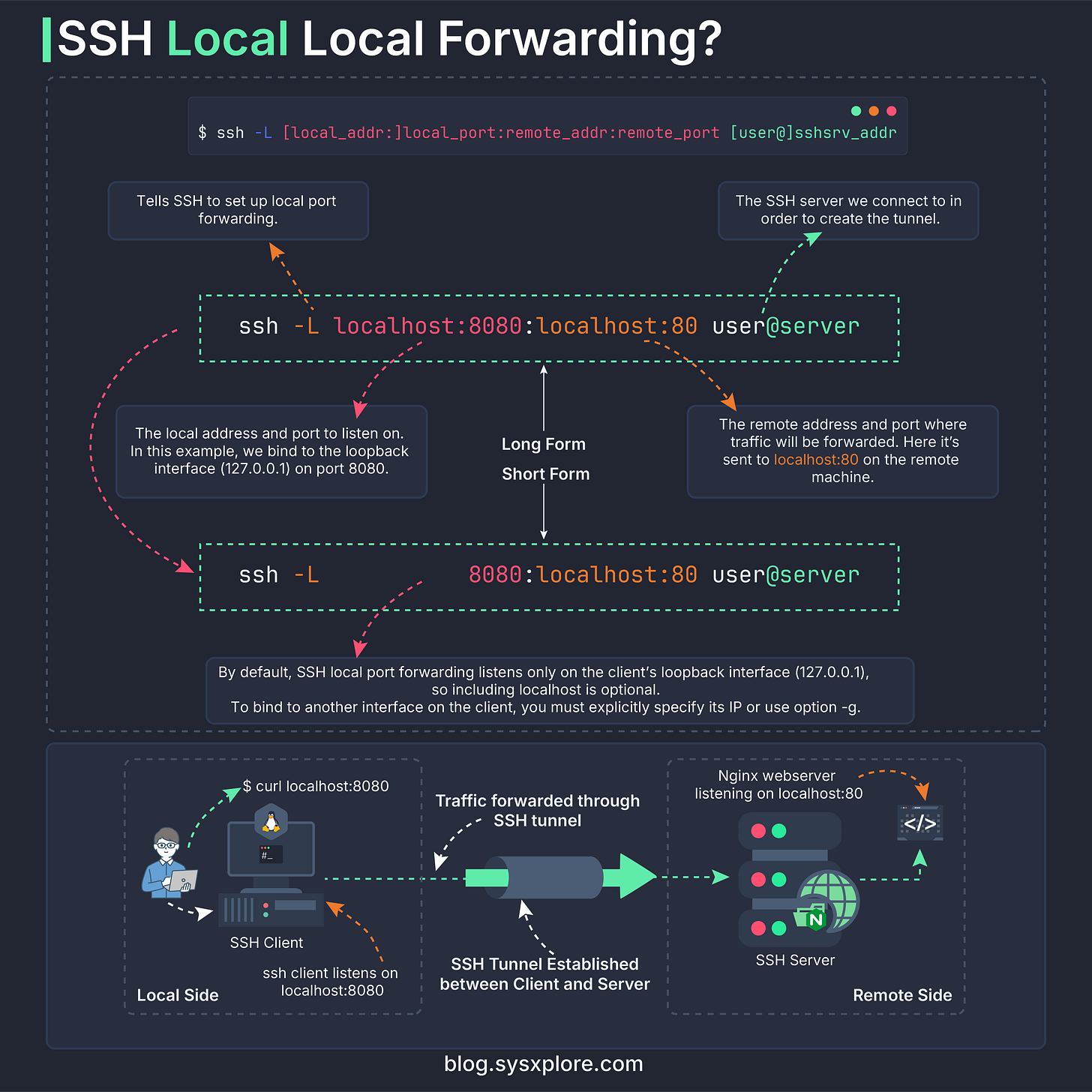

$ ssh -L <local_host>:<local_port>:<remote_host>:<remote_port> user@remote_ssh_serverWe’ll break this down properly in a moment. For now, let’s run the actual command on the client to create the tunnel:

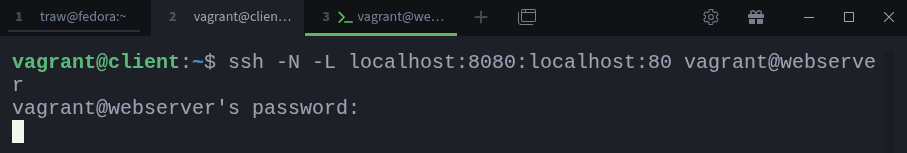

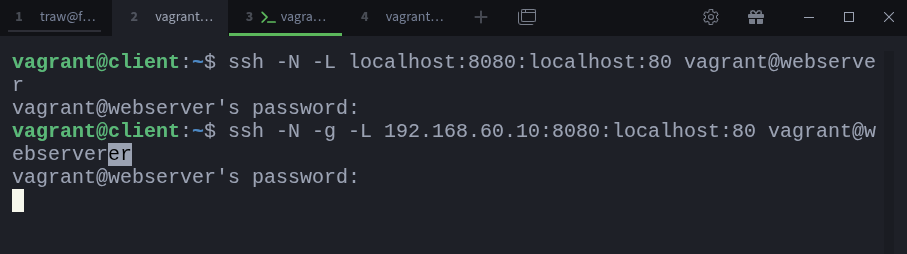

$ ssh -N -L localhost:8080:localhost:80 vagrant@webserverThis is a good time to explain what each part means:

-L tells SSH that we’re setting up local port forwarding.

localhost:8080 means we want to open port 8080 on our local machine (the client).

localhost:80 means that any traffic sent to localhost:8080 on the client should be forwarded to localhost on port 80 on the webserver from the webserver’s perspective.

vagrant@webserver is simply the SSH server we’re creating the tunnel to, which in this case is the webserver itself.

You also probably noticed the -N option:

-N tells SSH not to execute any remote commands. We only want the tunnel, not a remote shell.

If we removed -N, SSH would log us into a shell session after establishing the tunnel, which isn’t what we want here. We only need the tunnel.

Once the tunnel is established, SSH appears to “hang”, but that’s normal. It’s not stuck; it’s simply waiting for traffic to arrive on port 8080.

So we switch to a new terminal window to test it.

Verifying the Tunnel

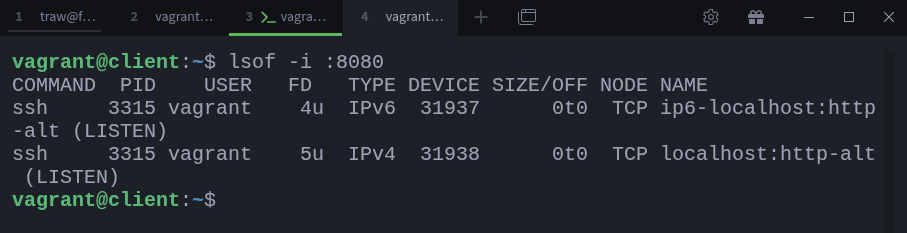

In the new terminal window, let’s confirm that SSH is listening on port 8080 on the client:

$ vagrant ssh client

$ lsof -i :8080You can see that the SSH process is listening on both IPv4 and IPv6 localhost on port 8080 (http-alt). We can also confirm that the SSH connection to the webserver is active:

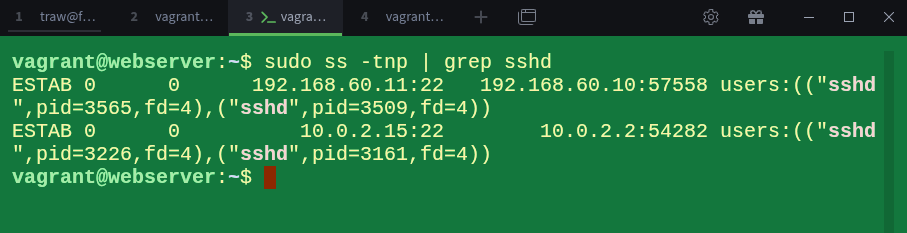

$ sudo ss -tnp | grep sshdThe first line shows the important part, our client (192.168.60.10) is connected to the webserver (192.168.60.11) over SSH. This confirms that the tunnel is active and ready.

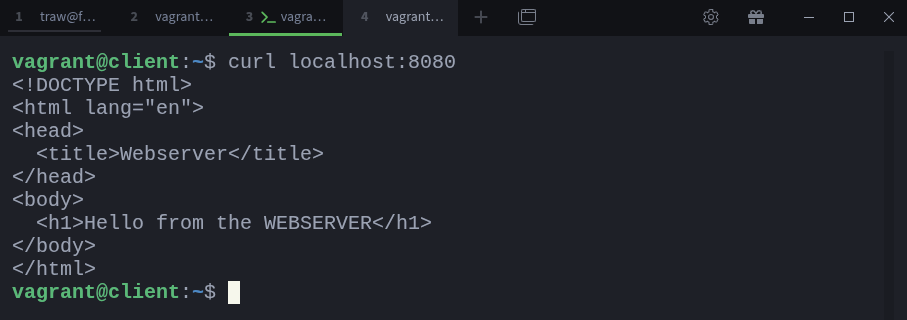

Now, let’s try to access the webserver through the tunnel by sending a request to localhost:8080 on the client:

$ curl localhost:8080And there we go, the tunnel works. The traffic was forwarded from our local port 8080 to the webserver’s port 80 via the SSH connection, bypassing the firewall restrictions.

Understanding the Two “localhost” Values

Before we move forward, there’s one point I really need to stress. A lot of people get confused about the two localhost values in the ssh -L command. So let’s clear that up properly.

The first localhost:8080 refers to your local machine, the client where you are running the SSH command. This is the port you are opening on your own computer. You can even simplify it and write just 8080 instead of localhost:8080:

$ ssh -N -L 8080:localhost:80 vagrant@webserverIt works the same way. When you don’t specify an address for the local bind, SSH automatically uses the loopback interface (localhost). This is because, by default, SSH local port forwarding listens only on the client’s loopback interface (127.0.0.1), so including localhost is optional. To bind to another interface on the client, you must explicitly specify its IP or use option -g. This is useful if you want other machines to access the forwarded port on your laptop.

For example, I will terminate the previous tunnel by pressint CTRL+C and run the following:

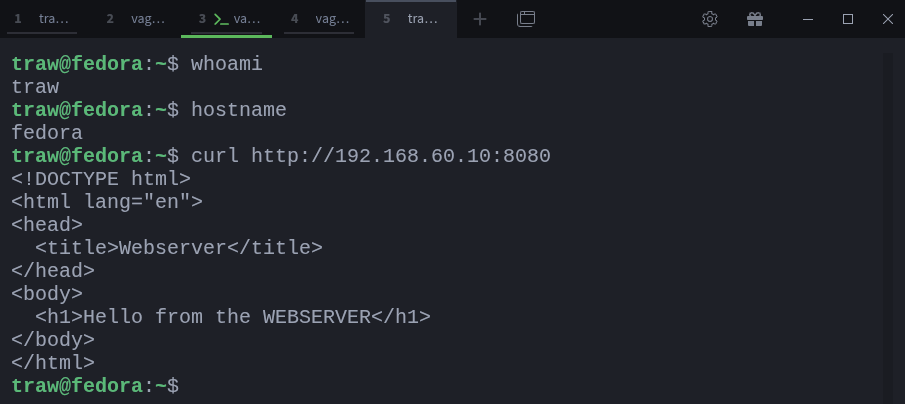

$ ssh -N -g -L 192.168.60.10:8080:localhost:80 vagrant@webserverThis will allow other machines on the same network to access port 8080 on your laptop (client). And the traffic will still be forwarded to the webserver’s port 80 via the SSH tunnel. Let’s test that using my host machine:

$ curl http://192.168.60.10:8080And it works! The traffic is successfully forwarded through the SSH tunnel.

The second localhost:80 refers to the target (destination) machine from the perspective of the SSH server. In this case, the SSH server is the webserver, so localhost on that side means the webserver itself. If the service were running on a different machine behind the SSH server, then you would replace localhost with that machine’s hostname or IP address. You’ll see exactly how this works when we cover SSH tunneling through a bastion host.

Visualizing the Traffic Flow

It’s one thing to run the command and see it work, and another to picture how the traffic actually moves. This diagram breaks the flow down step by step, from the client listening on port 8080, through the SSH tunnel, and finally to the service running on the remote machine.

Quick Tip

When you create an SSH tunnel, the session normally sits in the foreground and keeps your terminal busy. If you don’t want that, you can send the tunnel straight to the background by adding the -f option:

$ ssh -f -N -g -L 192.168.60.10:8080:localhost:80 vagrant@webserverThe -f flag tells SSH to move itself into the background just before running the command. This is handy when SSH will still prompt for a password or passphrase, but you don’t want the tunnel occupying your terminal afterward.

The only difference is how you stop it. When you run a tunnel in the foreground, you can simply press CTRL + C to close it. But once it’s in the background, you need to terminate the process manually.

You can find the process ID of the tunnel like this:

$ lsof -i :8080Note the PID from the output, then end the tunnel with:

kill <PID>This cleanly shuts down the background SSH tunnel without affecting anything else.

Looking Ahead

What we’ve covered here is only the first piece of what SSH tunnels can do. Local port forwarding gives you a private path into a service behind the SSH server, but there are situations where the direction needs to be reversed.

In the next part of this series, we’ll look at that opposite pattern, Remote Port Forwarding, and see how it lets a remote machine reach something running on your local system, even if you’re behind NAT or a firewall.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this content, don’t forget to leave a comment, like ❤️ and subscribe to get more posts like this every week.

good stuff!

Nice, neat and cool 😎. Another point worth mentioning is the fact that the SSH server establishes a TCP connection to the webserver (any remote host) and forwards the raw data from the client to it, making it protocol agnostic and hence support various protocols!